Four Decades Later, Local Vietnam Vets Step Out of Shadows

By Bill Slocum

Contributing Editor

Contributing Editor

The three men at a table in

Stamford’s City Limits diner have two things in common. All served their

country in Vietnam, seeing extensive combat; all eventually settled in

Greenwich, where each has lived for years.

Until now, they never met.

“I never knew there would be another

Vietnam veteran in Greenwich,” says Roger Paulmeno, who went on scout

patrols with the First Air Cavalry as a helicopter door gunner until a

phosphorous grenade burned much of his body and took him out of action

five months and one day into his tour of duty.

“It’s not the kind of town where people

went to Vietnam,” adds Ed Vick, like Paulmeno an Old Greenwich resident

who cruised the Mekong Delta in a Navy patrol boat during his second

Vietnam tour, from 1968-69.

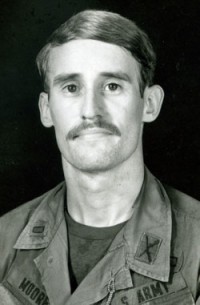

Bob Moore, a central Greenwich resident

for over 30 years who recently relocated to Stamford, patrolled the

jungle highlands outside Da Nang as an Army foot soldier. “I was pretty

heavily involved with the Greenwich Boy Scouts,” he says. “A lot of

those guys had military backgrounds, but no one else I knew of served in

Vietnam.”

Vietnam veterans have lived in Greenwich

since before the end of the war, if quietly. Bruce Winningham, head of a

local organization dedicated to servicing veterans, the Greenwich

Military Covenant for Care, has identified at least 50 Vietnam veterans

in town, and reports the sense of isolation described by Paulmeno, Vick,

and Moore is not unusual. Winningham says the local Vietnam veterans he

has met tend not to know one another’s names.

|

| Lt. Moore takes a break in the fighting somewhere in the jungle west of Chu Lai, with staff sergeant Roger Howard, sitting on their helmets in the mud. (photo contributed) |

Vietnam experiences were something the

veterans themselves were not eager to share for a long time after

returning. “By the time I moved to Greenwich, in 1972, I had learned,

sadly, that it was smarter not to talk about it, if you wanted to have a

job or friends,” says Vick, who for years worked in advertising at

Young & Rubicam.

Moore, a retired financial software

developer, was only a little less reticent. “I don’t think I was ever

reluctant to tell my story if the subject came up, but I never

volunteered it,” he says.

Today, however, the floodgates are open.

The three men swap stories in their collective ’Nam argot about misread

MOS, unreliable ARVN, and close encounters with B-40s. Often the room

fills with boisterous laughter.

The three men’s service in Vietnam

dovetailed in two different ways. First, each fought the war

differently—Moore on land, Vick on water, and Paulmeno in the air.

Second, they served near-consecutive but never simultaneous tours, Vick

from 1967-69, Paulmeno from February to July, 1970, and Moore from

November, 1970 to late 1971.

At one point in their three-way

conversation, Vick and Paulmeno realize they are talking about combat in

the same place, a wedge of Cambodia extending into the South Vietnamese

province of Tây Ninh, known as “the Parrot’s Beak.”

“It was a hotbed of activity,” explains

Vick, who patrolled the riverine network around the Beak in the anxious

months after a momentous North Vietnamese attack known as the Tet

Offensive. “That was their principal conduit into Saigon, and they could

travel it with impunity.”

|

| Sgt. Paulmeno at the door of his light-observation helicopter, where he was stationed as a gunner. (photo contributed) |

When Paulmeno flew over there on July 4,

1970, the Beak had calmed down a little, enough that he was surprised to

spot soldiers camped out in a supposedly off-limits area.

Then he realized they weren’t American

soldiers, but Chinese. A battle commenced, with Sgt. Paulmeno’s tiny

light observation helicopter doing its usual job of drawing fire so that

a bigger Cobra copter it flew in tandem with could pick out targets to

shoot at. The Cobra ran out of ammunition; all Paulmeno had left was a

phosphorous grenade, which he threw out the side of his copter. For some

reason, it flew back in, landing in Paulmeno’s lap.

By the time he had thrown the sputtering

explosive back outside, he had sustained extensive burns to his arms,

legs, and face. Instantly he lost his vision, which would only return

partially over time and would leave his irises clouded over. The

fingertips of his right hand were destroyed; today those fingers remain

shortened and deformed.

“I think on one hand I’m luckier than

these guys, only because of what happened to me,” Paulmeno says.

“Because I have the scars to prove something happened.”

The other two experienced culture shock, going from a battle zone to civilian life in a matter of hours.

Vick recalls attending college after his

return from Vietnam, where an instructor in one classroom pointed out

Vick’s service to the class. For a month and a half, the other 34

students ignored him.

“They completely froze me out,” he says.

“Finally, I ended up talking to the craziest guy in the class, and

broke down some barriers. I said: ‘What was that about?’ He said: ‘We

figured you were a rapist and a baby-killer, because that’s what we

hear.’”

In fact they were survivors, having seen

violence close up, losing friends, and fighting to stay alive. Instincts

honed in battle did not soon go away.

“My wife tells a funny story,” Moore

says. “I was freshly back, and with one of my buddies who had been in

the 101st (Airborne Division) in Vietnam at my apartment on 57th Street.

A car backfires, and instantaneously this guy and I both go over a

couch and lie flat on the floor.”

On his PBR (Patrol Boat, River), Vick, a

Navy lieutenant junior grade, cruised narrow brown-water rivers in

search of the enemy. Firefights occurred every couple of days, he

recalls, the enemy usually opening up all of a sudden. “The noise is so

deafening, it’s almost like silence because it’s so loud,” he says. The

rivers were often so narrow, a PBR had no choice but to race through

fields of fire as quickly as possible.

“My first firefight, my boat was sunk right underneath me,” Vick recalls. “It was a rude awakening.”

For his part, Moore, an Army lieutenant,

remembers firefights occurring “once a week,” with the enemy suddenly

opening fire from just a few yards away. “You were right on top of them

when you engaged them,” he says. “We were trying to do our mission, and stay alive, and watch our buddies’ backs.”

As dangerous as patrol duty was, Moore

says his most hazardous posting was in the rear, with the battalion

support company. “Everyone was very straight out in the jungle,” he

says. “But in the rear area, you had to worry about a crazy guy rolling a

grenade into your tent at night.”

As the three men talked, they disagreed on one point: Who had it worse.

For his part, Moore marvels at the

helicopters who flew into firefights to rescue wounded soldiers. Vick

says he felt safer on a boat that he would have on land.

“I felt good I wasn’t these guys,” Paulmeno says. “Because we could fly away. They were stuck.”

Paulmeno has spent the last 35 years

working with other Vietnam veterans, as a therapist with the Vet Center

in White Plains, N.Y. Even when he was in a hospital recovering from his

wounds, he was asked to look after other patients. He says his own

recovery began there.

“I’ve been hearing stories for 30 years,” he says. “My own story wasn’t Vietnam, it was the hospital.”

For Vick and Moore, the road back started

in the mid-1980s. That was when efforts to recognize the service of

Vietnam War veterans began in earnest, especially after construction of

the Vietnam War Memorial in 1982.

“The Wall, I think, was the turning

point,” says Moore, referring to the Memorial’s popular designation.

“Until the Wall went up, there wasn’t the affirmation of our service.”

Vick describes himself as being “in the

closet” about Vietnam until about that time, when he got involved with

the New York Vietnam Veterans Memorial Commission.

In recent years, both Vick and Moore have

been helping veterans of a later era. Moore sent care packages to

troops in Iraq and Afghanistan. Vick works in a program called “Give An

Hour,” connecting returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans suffering from

post-traumatic stress disorder with social workers who donate their

time one hour at a time. Vick also puts in time escorting World War II

and Korean War veterans to honor ceremonies.

“I have been working with Iraq and

Afghanistan veterans for ten years,” Vick says. “I have to tell you,

maybe because all these years I’m looking for something about Vietnam to

feel good about, but it makes me feel good. You always want to make a

difference.”

Today, the Greenwich Military Covenant

for Care works with Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in town looking for

help readjusting to civilian life. “We had one of our young men who was

raised in town and served in Iraq,” says Mary Jane Huffman, a volunteer

with the Covenant. He said: ‘People welcomed me, they thanked me for my

service, and I don’t think that would have happened had people not learned from Vietnam.’”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.